Common name: Breadfruit

Other common names: Ulu

Description

Breadfruit is one of the most important food trees of the tropics, the fruit being a staple for many and, as its name suggests, is a substitute for bread.

Originating in the Old World tropics, the tree's natural range extends from Malaysia, through Indonesia and Papua New Guinea, to Polynesia in the Western Pacific.

Breadfruit can be separated into two main types, seeded and non-seeded. Non-seeded types, also known as sterile types, are the most widely eaten and the focus of this description.

It may grow into a large tree up to 30 m (100 ft) in height, though it is typically between 15 and 20 m (50 to 65 ft) tall with a straight trunk supporting a densely leafy rounded crown. The bark is grey-brown, smooth on young trees, with age becoming mottled, cracked and rough, and on wounding yields a sticky white latex, as do all parts of the tree.

Leaves are large, up to 30 cm (12 in) across, deeply lobed, on top dark glossy green, underneath pale dull green. Although the tree is evergreen, leaf exchange occurs continuously throughout the year. The old leaves turn first yellow, then brown and papery, before falling to the ground.

Flowers are small and insignificant, held in clusters of male or female flowers on the same tree. The male flowers are tightly packed in club-shaped spikes up to 30 cm (12 in) long, the female flowers in smaller oval-shaped spikes, and there are up to two thousand flowers on each spike.

Flowering is continuous in humid climates, but fruiting is most abundant in the rainy season and in the two to three months that follow. The fruit are oval to round and large, up to 20 cm (8 in) in diameter. When young, they have bright green skin, becoming dull green with age and with brown mottling caused by droplets of latex drying on the surface.

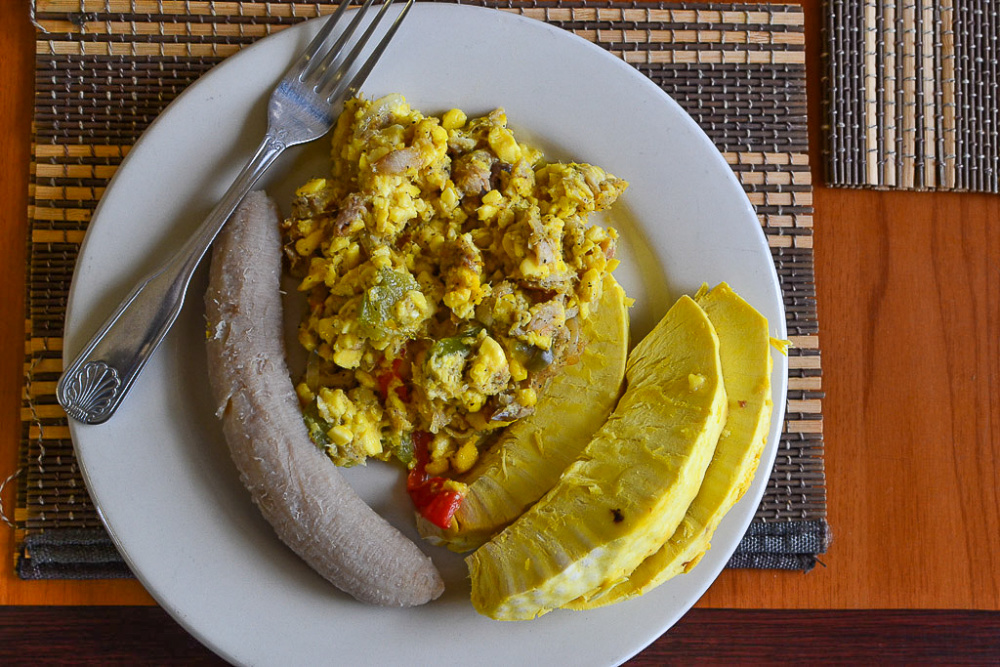

There are many varieties of seedless breadfruit, varying in fruit shape and size, as well as leaf shape and size. However, most commonly, they are distinguished by the colour of their pulp, which has given rise to two named types, 'White heart' and 'Yellow heart'.

Mature breadfruit

Use

For most uses, the fruit is harvested at the mature but still unripe stage, when the pulp is firm and has not yet softened, as it becomes near-liquid in its consistency when fully ripe.

The most popular way of preparing mature breadfruit is by roasting it whole in the skin, especially over hot coals. This chars and blackens the skin, which is then peeled off, leaving behind the steaming white or pale yellow pulp. Slightly sweet and spongy, the cooked pulp is eaten like warm, freshly baked bread, sometimes even being spread with butter.

In the French-speaking Caribbean, the boiled pulp is mashed, seasoned and formed into small balls stuffed with meat or other ingredients, then crumbed and fried to a golden crisp. Known as 'Boulettes', they are a popular snack or starchy accompaniment to a meal. Breadfruit croquettes are similarly made by altering or simply leaving out some of the ingredients.

Boiled and diced breadfruit is also used for making mock potato salad by substituting the diced or cubed breadfruit for potato and then mixing this with a mayonnaise-based sauce.

The pulp of mature fruit can be dried and ground to make a gluten-free flour suitable for mixing with other flours to make bread, cakes and other baked goods. Breadfruit flour contains about 4% protein. Although less than enriched wheat flour (at about 10%), it has higher levels of the essential amino acids lysine and threonine.

Some recipes call for 'green' or not yet fully mature fruit, at the stage when the pulp is starchy but still supple enough to be thinly sliced. Such as when making breadfruit chips, a popular snack wherever the breadfruit is found. Air-drying the thin slices for about an hour before frying reduces their oil absorption by almost half, reducing their calorie content.

The pulp of fully ripe fruit is sweet, soft, almost runny, and can be used in fillings for pies and other pastries, or when in abundance, makes a good livestock feed.

The milky latex is reportedly a good substitute for chicle used in making chewing gum. Chicle is sourced from the Sapodilla tree (Manilkara zapota).

Roasted breadfruit

Peeled roasted breadfruit

General interest

During breadfruit season in the Caribbean, bakeries experience a significant fall in bread sales and must plan their production accordingly.

Climate

Breadfruit grows and fruits reliably in humid tropical climates, generally frost-free areas with annual lows of 18 to 25°C, annual highs of 27 to 35°C, annual rainfall of 1200 to 4500 mm, and a dry season of 5 months or less.

Breadfruit trees fail to thrive in areas where the average low of the coldest month is below 16°C (60°F).

Growing

New plants are usually started from cuttings or root suckers, as seed are generally not produced. Circumposing (air-layering) new branches also give good results.

Cuttings and suckers do best potted in a free-draining potting mix made of coarse, pH-neutral materials, with coir, river sand and sawdust the components most commonly used. The plants are then cared for under shade in a nursery and misted in dry weather until they are about 0.6 to 1.6 m (2 to 5 ft) tall or 5 to 9 months old. They mature quickly and start to bear fruit 3 to 5 years after planting out.

Breadfruit trees perform best on deep, fertile, free-draining clay, loam and sand soils of a moderately acid to slightly alkaline nature, generally with a pH of 6.0 to 7.5, and on sites with full sun exposure.

Problem features

Breadfruit is assessed as a low weed risk species for Hawaii by the Hawaii Pacific Weed Risk Assessment (HPWRA) project. There does not appear to be any records of it anywhere as a weed or invasive species, despite being introduced long ago in regions outside of its native range.

Fully ripe breadfruit detach from the tree and fall to the ground where they splatter, creating a sticky, messy litter, as do the fallen leaves.

Where it grows

References

Books

-

Adams, C. D. 1972, Flowering plants of Jamaica, University of the West Indies, Mona, Greater Kingston

-

Allen, B. M. 1967, Malayan fruits : an introduction to the cultivated species, Donald Moore Press, Singapore

-

Elevitch, C. R. & Thaman, R. R. 2011, Specialty crops for Pacific islands, 1st ed, Permanent Agriculture Resources, Hawaii

-

Fellows, P. 1997, Traditional foods : processing for profit, Intermediate Technology, Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Co-operation, London

-

Francis, J. K. and Liogier, H. A. 1991, Naturalized exotic tree species in Puerto Rico, General technical report SO-82, USDA Forest Service, Southern Forest Experiment Station, New Orleans

-

Francis, J. K. et al. 2000, Silvics of Native and Exotic Trees of Puerto Rico and the Caribbean Islands, Technical Report IITF-15, USDA Forest Service, Rio Piedras, Puerto Rico

-

Jensen, M. 1999, Trees commonly cultivated in Southeast Asia : an illustrated field guide, 2nd ed., Food and Agricultural Organisation of the United Nations (FAO) Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific (RAP), Bangkok

-

Macmillan, H. F. 1943, Tropical planting and gardening : with special reference to Ceylon, 5th ed, Macmillan Publishing, London

-

Mollison, B. 1993, The permaculture book of ferment and human nutrition, Tagari Publications, Tyalgum, New South Wales

-

Morton, J. F. & Dowling, C. F. 1987, Fruits of warm climates, Creative Resources Systems, Winterville, North Carolina

-

Page, P. E. 1984, Tropical tree fruits for Australia, Queensland Department of Primary Industries (QLD DPI), Brisbane

-

Perry, F. & Hay, R. 1982, A field guide to tropical and subtropical plants, Van Nostrand Reinhold Company, New York

-

Queensland Department of Primary Industries and Fisheries (QLD DPI) 2008, Queensland tropical fruit : the healthy flavours of North Queensland, Brisbane

-

Selvam, V. 2007, Trees and shrubs of the Maldives, Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) RAP publication (Maldives), Thammada Press Company Ltd., Bangkok

-

Van Wyk, B. E. 2005, Food plants of the world: an illustrated guide, 1st ed., Timber Press, Portland, Oregon

-

Wenkam, N.S. 1983 to 1990, Foods of Hawaii and the Pacific Basin (5 volumes), College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources, University of Hawaii, Honolulu

Articles, Journals, Reports and Working Papers

-

Hamilton, R.A. 1987, Ten tropical fruits of potential value for crop diversification in Hawaii, Research Extension Series : RES-085, University of Hawaii, Honolulu

-

International Plant Genetic Resources Institute (IPGRI) 1996 to 1998, Promoting the conservation and use of underutilized and neglected crops (Series of 24 publications), IPGRI, Rome

-

Subhadrabandhu, S. 2001, Under-utilized tropical fruits of Thailand, Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO), Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific (RAPA), Bangkok

-

Watson, B.J., & Moncur, M. 1985, Guideline criteria for determining survival, commercial and best mean minimum July temperatures for various tropical fruit in Australia (Southern Hemisphere), Department of Primary Industries Queensland (DPI QLD), Wet Tropics Regional Publication, Queensland

-

Wenkam N.S. & Miller C.D. 1965, Composition of Hawaii fruits (Bulletin 135), University of Hawaii, Honolulu